Cessna gets caught with its hand in the FAA’s cookie jar.

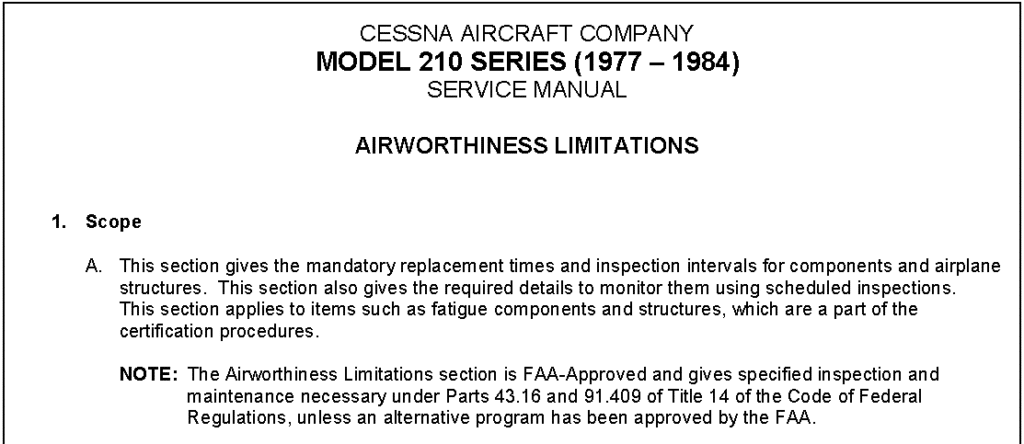

On February 10, 2014, the Cessna Aircraft Company did something quite unprecedented in the history of piston GA: It published a revision to the service manual for cantilever-wing Cessna 210-series airplanes that added three new pages to the manual. Those three pages constituted a new section 2B to the manual, titled “Airworthiness Limitations”:

This new section purports to impose “mandatory replacement times and inspection intervals for components and aircraft structures.” It states that the new section is “FAA-Approved” and that compliance is required by regulation.

Indeed, FARs 91.403(c) and 43.16 both state that if a manufacturer’s maintenance manual contains an Airworthiness Limitations section (ALS), any inspection intervals and replacement times prescribed in that ALS are compulsory. FAR 91.403(c) speaks to aircraft owners:

§91.403(c) No person may operate an aircraft for which a manufacturer’s maintenance manual or instructions for continued airworthiness has been issued that contains an Airworthiness Limitations section unless the mandatory replacement times, inspection intervals, and related procedures specified in that section … have been complied with.

and FAR 43.16 speaks to mechanics:

§43.16 Each person performing an inspection or other maintenance specified in an Airworthiness Limitations section of a manufacturer’s maintenance manual or Instructions for Continued Airworthiness shall perform the inspection or other maintenance in accordance with that section…

Sounds pretty unequivocal, doesn’t it? If the maintenance manual contains an ALS, any mandatory inspection intervals and replacement times have the force of law.

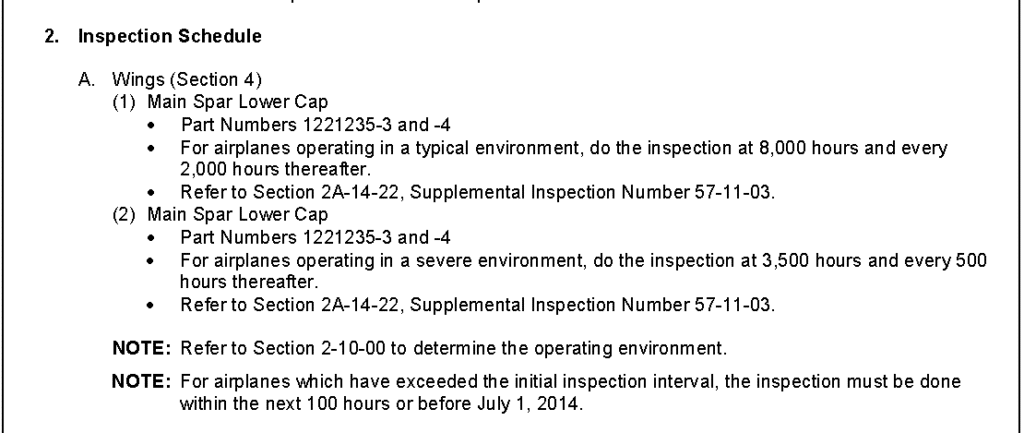

The new ALS in the Cessna 210 maintenance manual mandates eddy-current inspection of the wing main spar lower caps. For most 210s, an initial spar inspection is required at 8,000 hours, with recurring inspections required every 2,000 hours thereafter. However, for 210s operated in a “severe environment” the inspections are required at 3,500 hours and every 500 hours thereafter:

For P210s, the new ALS also imposes a life limit of 13,000 hours on the windshield, side and rear windows, and ice light lens.

What’s wrong with this picture?

To be fair, the eddy-current inspection is not that big a deal. An experienced technician can do it in a few hours. The most difficult part is that most service centers have neither the eddy-current test equipment nor a trained and certificated non-destructive testing (NDT) technician on staff. So most Cessna 210 owners will need to fly their airplane to a specialty shop. Since most airplanes will need to do this only once every 2,000 hours and since most of them fly less than 200 hours per year, one could hardly classify this recurrent eddy-current inspection as Draconian. Similarly, not too many P210s are likely to reach the 13,000-hour life window life limit.

No, the issue isn’t the spar cap inspection or window life limits themselves—it’s the extraordinary method by which Cessna attempted to make them compulsory for aircraft owners to perform.

Normally, if the manufacturer of an aircraft, engine or propeller wants to impose a mandatory inspection interval or a mandatory replacement or overhaul time on the owners of its aeronautical product, the manufacturer goes to the FAA and requests that an Airworthiness Directive (AD) be issued. If the FAA agrees and decides to issue an AD, it does so by means of a formal rule-making process prescribed by the federal Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Ultimately, the AD is published in the Federal Register and becomes an amendment to Part 39 of the FARs. That’s what gives the AD its “teeth” and makes it compulsory for aircraft owners to comply with it.

§91.403(a) The owner or operator of an aircraft is primarily responsible for maintaining that aircraft in an airworthy condition, including compliance with part 39 of this chapter.

The APA governs the way that all executive-branch regulatory agencies of the federal government (including the FAA) may propose and establish regulations. It has been called “a bill of rights” for Americans whose affairs are controlled or regulated by federal government agencies. The APA requires that before a federal agency can establish a new regulation, it must publish a notice of proposed rule making (NPRM) in the Federal Register, provide members of the public who would be impacted by the proposed regulation an opportunity to submit comments, and then take those comments seriously in making its final rule. The APA also establishes rights of appeal if a person affected by the regulation feels it is unjust or should be waived.

Because of the APA and other federal statutes, it is difficult for the FAA to issue ADs arbitrarily or capriciously. The agency first has to demonstrate that a bona fide unsafe condition exists, and that its frequency and severity of the safety risk rises to the level that makes rule making appropriate. It has to estimate the financial impact on affected owners. It has to provide a public comment period, give serious consideration to comments submitted, and respond to those comments formally when issuing its final rule.

As someone who has been heavily involved in numerous AD actions on behalf of various alphabet groups, I can tell you that the notice-and-comment provisions of the APA is extremely important, and that concerted efforts by aircraft owners and their representative industry organizations have often had great impact on the final outcome.

Through the back door?

That’s what made Cessna’s action in February 2014 so insidious.

The addition of an Airworthiness Limitations section to the Cessna 210 maintenance manual was done without going through the rule making process. There was no NPRM and no comment period. Affected owners never had an opportunity to challenge the need for eddy-current inspections of their wing spars. Cessna was never required to demonstrate that a genuine unsafe condition exists, nor weigh the cost impact against the safety benefit. By adding an ALS to the maintenance manual, Cessna was attempting to bypass the APA-governed AD process and to impose its will on aircraft owners “through the back door.”

Granted that the initial contents of the new ALS is not excessively burdensome. But if Cessna’s unprecedented action were allowed to go unchallenged, it would set a terrible precedent. It would mean that any aircraft, engine or propeller manufacturer could retroactively impose its will on aircraft owners.

In which case, Katy bar the (back) door!

David vs. Goliath

I first learned about this at the beginning of September 2014, when my colleague Paul New—owner of Tennessee Aircraft Services, Inc. (a well-known Cessna Piston Aircraft Service Center) and honored by the FAA in 2007 as National Aviation Maintenance Technician of the Year—discovered the new section 2B in the Cessna 210 service manual, and immediately realized its significance. Paul and I discussed the matter at length, and both felt strongly that Cessna’s actions could not be allowed to go unchallenged.

“If Cessna gets away with this,” I told Paul, “than any manufacturer will be able to effectively impose their own ADs whenever they want, bypassing the notice-and-comment protocol and the other safeguards built into the APA to protect the public from unreasonable government regulation.”

I helped Paul draft a letter to the Rulemaking Division (AGC-200) of the FAA’s Office of General Counsel, questioning the retroactive enforceability of Cessna’s newly-minted ALS against Cessna 210s that were manufactured prior to the date the ALS was published (i.e., all of them, given that Cessna 210 production ceased in 1986). Our letter questioned whether Cessna could do what it was trying to do (i.e., make the eddy-current inspections compulsory) within the confines of the APA. We asked AGC-200 to issue a formal Letter of Interpretation (LOI) of the thorny regulatory issues that Cessna’s unprecedented actions raised.

And then we waited. And waited.

FAA Legal Does the Right Thing

AGC-200 initially advised us that they had a four-month backlog of prior requests before they would be able to respond to our request. In fact, it took seven months. It turns out that our letter questioning the enforceability of Cessna’s ALS opened a messy can of worms. AGC-200 assigned two attorneys to draft the FAA’s response, and they wound up having to coordinate with AFS-300 (Flight Standards Maintenance Division), AIR-100 (Aircraft Certification Division), ACE-100 (Small Airplane Directorate), and of course ACE-115W (Wichita Aircraft Certification Office) who mistakenly approved Cessna’s ALS in the first place.

Finally, on May 21, 2015, AGC-200 issued the Letter of Interpretation (LOI) that we requested. It was five pages long, and was everything we hoped it would be and more. It slammed shut the “rulemaking backdoor” that Cessna had been attempting to use to bypass the AD process, locked it once and for all, threw away the key, and squirted epoxy glue in the lock for good measure. You can read the entire LOI in all its lawyerly glory by clicking here.

But, here’s the CliffsNotes version of the letter’s key bullet points:

- Under FAR 21.31(c), an ALS is part of an aircraft’s type design.

- The only version of an ALS that is mandatory is the version that was included in the particular aircraft’s type design at the time it was manufactured.

- Absent an AD or other FAA rule that would make the new replacement times and inspection intervals retroactive, Cessna’s “after-added” ALS is not mandatory for persons who operate or maintain the Model 210 aircraft, the design and production of which predate the new ALS addition. The “requirements” set forth in the ALS would only be mandatory for aircraft manufactured after the ALS was issued. And of course, production of the Cessna 210 ceased in 1986.

- If operational regulations were interpreted as imposing an obligation on operators and maintenance providers to comply with the latest revision of a manufacturer’s document, manufacturers could unilaterally impose regulatory burdens on operators of existing aircraft. This would be legally objectionable in that the FAA does not have legal authority to delegate its rulemaking authority to manufacturers. Furthermore, “substantive rules” can be adopted only in accordance with the rulemaking section of the APA (5 U.S.C. § 553) which does not grant rulemaldng authority to manufacturers. To comply with these statutory obligations, the FAA would have to engage in its own rulemaking to mandate the manufacturer’s document, as it does when it issues ADs.

The bottom line is this: Manufacturers of certificated aircraft* are not permitted to impose regulatory burdens on aircraft owners by changing the rules in the middle of the game. Only the FAA may do that, and only through proper rulemaking action that complies with the APA (including its notice-and-comment provisions and other safeguards). If you ever encounter a situation where the manufacturer of your aircraft tries to do this, call their cards—the FAA lawyers will back you up.

*NOTE: The rules are completely different for S-LSAs. The manufacturers of S-LSAs can do pretty much anything they like, and their word is the law. (A seriously flawed situation IMHO.)

The LOI concluded with the following surprising paragraph:

On February 19, 2015, the FAA’s Small Airplane Directorate sent a letter to Cessna that addressed some of the above issues, and pointed out the non-mandatory nature of the after-added ALS for the Model 210 aircraft. The FAA asked Cessna to republish the replacement times and inspections as recommendations that are encouraged, but optional, for those in-service aircraft, unless later mandated by an AD. To date [three months later –mb] Cessna has not provided a written response outlining its position on this matter.

Hopefully by the time you read this, Cessna will have responded to FAA HQ, agreed to remove its rogue ALS, and promise never to try such backdoor rulemaking again.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: