“During an attempt to dial the prop flange of the Lycoming O-540 in my 1968 Piper PA-28-235 Pathfinder, it was noticed the crankshaft would chatter while rotating it slowly,” Frank said in his initial post to a SavvyQA ticket. “My mechanic says ‘it feels like stiction.’ It’s fairly uniform relative to the crank position during rotation. We were rotating the crank thru two adjacent bolts threaded into the flange and using an 18-inch pry bar.”

Savvy account manager Brandon Thompson A&P/IA quickly responded. He asked Fred what steps had been taken so far to isolate what was causing the crankshaft to stick.

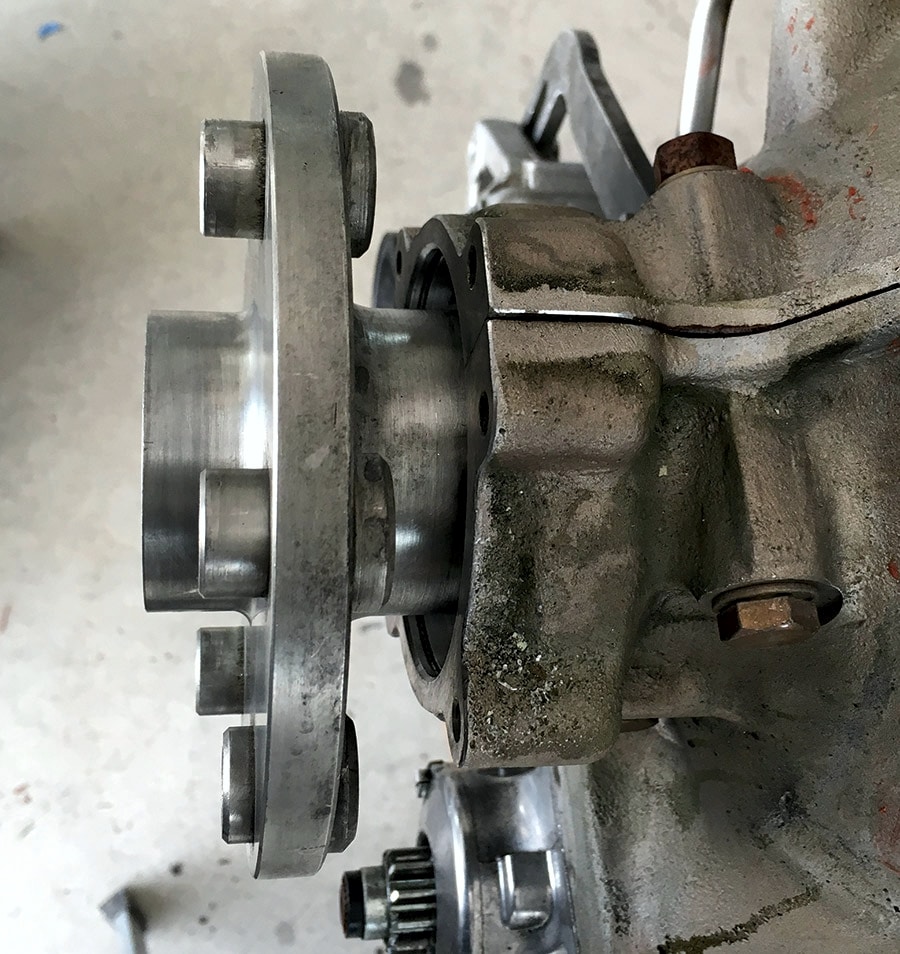

“We removed the spark plugs, of course, so there’s no compression opposing crankshaft rotation,” Frank said. “We borescoped the cylinders but did not see anything extraordinary. We’ve now removed all engine accessories—vacuum pump, both mags, fuel pump, and prop governor—but the issue persists. Squirting some oil in each cylinder made it slightly smoother but did not appreciably diminish the stiction. My mechanic removed the oil screen to see if there was any metal present, and there wasn’t.”

Call On The Expert

Brandon felt it would be a good idea to solicit some additional brainpower from Savvy’s technical team, so he added Ryan Dickerson A&P/IA to Frank’s ticket. Ryan is one of Savvy’s resident engine experts, and co-owner of the nationally known engine overhaul facility Western Skyways in Montrose, Colorado.

Ryan reviewed Frank’s ticket. “This sounds to me like the rings are dragging in the cylinder walls,” Ryan posted to Frank’s ticket early the next morning. “Using an oil can to squirt oil through the top spark plug hole will put a little oil on the bottom of the cylinder and rings, but to get oil on the sides and top of the cylinder barrel, it’s really necessary to use a pressure sprayer to atomize a fine oil mist onto the cylinder walls. This should be done with the piston at the bottom of the stroke, and should be done through both top and bottom spark plug holes to obtain the most lubricant coverage.”

“Appreciate the feedback,” Frank replied. “I will share with the team and update during the day.”

Solved!

“That did it!” posted Frank that evening. “It was indeed ring drag. Per Ryan’s suggestion, after oiling all the cylinders top and bottom with a pressure sprayer, the crankshaft rotated smoothly. Thank you, Ryan!”

“Looking back now, the saddest part of this experience was that the local engine shop guru was there and he dialed the crank himself,” Frank reported. “He alerted us to the roughness but only instructed us to borescope the cylinders, which we did of course. The engine shop guy never thought to suggest lubricating the cylinders. That was when we started to pull off all the engine accessories trying to isolate the problem.”

“It was 18 man-hours later that out of desperation I decided to ask for help from Savvy,” Frank continued. “My biggest regret is not coming to you guys sooner. Thank you again. You are awesome!”

“I’m glad you solved it,” replied Brandon, “but sorry it wound up being so invasive. I hope your shop is willing to ‘eat’ some of that labor time. Removing and reinstalling all those accessories shouldn’t amount to anything close to 18 labor hours.”

“I’ve been with this mechanic now going on 18 years,” Frank said. “I will be negotiating with the shop and I’m confident they will be fair with the billing.”

“I can’t help but ask,” said Brandon, “Why were you dialing the crank to begin with? Did you have a prop strike?”

Brandon knew that the usual reason for measuring the prop flange for runout was to check for damage after a prop strike. He also knew that there’s an Airworthiness Directive affecting all Lycoming engines that requires the engine accessory case to be removed and the crankshaft gear attaching bolts replaced after any prop strike.

“No prop strike,” Frank explained. “The crank dialing was at my request when we were desludging the crankshaft bore at 600 hours. I was curious about possible flange runout because I just had the prop dynamically balanced a few weeks ago. It was supposed to be less than two hours of labor, and I asked for it to be done purely out of curiosity. Lesson learned.”

Frank’s lament—“My biggest regret is not coming to you guys sooner”—is one we hear a lot. As a SavvyQA subscriber, Frank has unlimited access to Savvy’s technical team of 20 veteran A&P/IA account managers with close to 400 years of GA maintenance experience between them. Our team includes experts in almost every conceivable aspect of maintenance: engines, electrical, avionics, sheet metal and composite repair, etc. We work as a team, and are quick to call in the relevant subject matter expert whenever the need arises.

As Frank’s experience illustrates, this often results in a quick pinpoint diagnosis and eliminates the need for costly “shotgunning.” It also illustrates the importance of getting Savvy involved early, before maintenance starts getting invasive and expensive.

At just $375 per year for a piston single—including unlimited maintenance consulting, engine monitor data analysis, and 24/7 breakdown assistance—we think SavvyQA is one of the best bargains in General Aviation. Wouldn’t you feel more confident knowing that Savvy’s whole team was available whenever you need help?

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: