Jim, Jack and Gene are members of the faculty at Indiana University in Bloomington. They are also partners in a 1968 Cessna 177 Cardinal based at Monroe County Airport (KBMG).The Cardinal was first introduced by Cessna in 1968 as a successor to the venerable 172 Skyhawk. It featured a cantilever (non-strut-braced) laminar flow wing, a stabilator, and a 150 horsepower Lycoming O-320 engine with a fixed-pitch prop. The new airplane turned out to have both handling and performance issues—it had an anemic climb rate and often porpoised during the landing flare.

Cessna addressed these problems in the 1969 model by adding a slot to the stabilator and changing to a 180 horsepower Lycoming O-360. All of the 1968 models got retrofitted with the slotted stabilator, and most were also upgraded via STC to the 180 horsepower engine. The Cardinal that Jim, Jack and Gene owned had both of these upgrades.

In late May, about 10 hours after the Cardinal had come out of its annual inspection, Gene decided to take a week off and fly the plane on a grand tour of the Southeast U.S. One of the stops on his itinerary was historic Richmond, Virginia. He filed for Richmond Executive Airport (KFCI) and made it there but just by the skin of his teeth.

As Gene related it, he was descending toward KFCI when the engine started to run really rough. Gene found that he could only get about 2,000 RPM at full throttle, barely enough to hold altitude. Fortunately, he was able to land safely. The FBO referred him to the largest maintenance shop on the field, Dominion Aviation, so Gene taxied the sick airplane there.

Preliminary Diagnostics

Jonathan Flory, one of the mechanics at Dominion, quickly determined that cylinder #2 had 0/80 compression. A borescope inspection revealed an exhaust valve that was stuck wide open and wouldn’t budge. The mechanic said that the #2 cylinder was going to have to come off and be overhauled or replaced. Gene approved removing the cylinder and replacing it with a new Superior Millennium cylinder. The mechanic put one on order.

The mechanic at Dominion removed the engine’s oil filter and cut it open to inspect the media for metal. He didn’t like what he saw:

The mechanic told Gene that it was going to be necessary to pull the engine and send it out to an engine shop for a teardown inspection to determine where the metal was coming from. This was starting to look like a $20,000 event, so Gene contacted his airplane partner Jim, who served as the maintenance officer for the group.

“Knowing that this was turning into a big deal I felt a little trapped,” Jim said. “I wanted the safest, most economical resolution to our dilemma.”

Time to Call the Hotline

Jim remembered that he’d enrolled the Cardinal in SavvyBreakdown, the $99/year breakdown assistance program offered by Savvy Aviation. It provides 24/7 assistance to Savvy’s team of highly experienced A&P/IA account managers in the event of an aircraft breakdown more than 50 miles from home base.

“Think of it as AAA for your airplane,” Jim said. “It’s a program that offers peace of mind, but one you hope you’ll never have to use.”

Now that the Cardinal was broken down 500 miles from home and a mechanic there was talking about having the engine torn down, Jim decided that he’d better call the SavvyBreakdown toll-free 24/7 hotline and ask for help.

“Our 1968 Cessna Cardinal is AOG at KFCI with a stuck #2 exhaust valve on its Lycoming O-360 engine,” Jim told the dispatcher who answered the call. Five minutes later, Jim received a call back from Tony Barrell A&P/IA, one of Savvy’s most experienced account managers. Jim briefed Tony on the situation, and about 30 minutes later Tony was in contact with Jonathan (the mechanic) and his boss, John Tagney (Dominion’s Director of Maintenance).

Savvy had worked with Dominion Aviation numerous times in the past, and Tony knew it to be a large and first-rate maintenance operation, but also a busy one that was usually booked up for weeks in advance. (Most of the best shops are usually booked up.)

“We have a client AOG at your field with a stuck valve,” Tony messaged Jonathan and John.. “Can you folks perform Lycoming SI 1425A?” (Tony was referring to a Lycoming service bulletin that describes a procedure for freeing up a sticking valve without having to remove the cylinder from the engine.) “It’s a pretty simple procedure. Let me know if you can help our client out, please.”

“We met with the pilot, Gene, and have confirmed that a valve is stuck on the #2 cylinder,” Jonathan replied to Tony. “Our understanding from the pilot is that this is not the first time. The options we presented the pilot were to overhaul the existing cylinder or replace the cylinder with a new one. The pilot elected to purchase a new Superior Millennium cylinder (part number SL36006W-A20P). We will install it when it arrives this week.”

Savvy hates to see cylinders removed unless there’s no alternative. We always urge our SavvyBreakdown clients to call the hotline BEFORE they authorize any repairs or replacement parts.

“Jim, did you approve a new cylinder?” Tony inquired.

“Tony, my partner Gene apparently okayed the cylinder replacement,” Jim said. “Sorry for the confusion.”

“No problem,” Tony said. “Things like that happen. You’ll need to break in the new cylinder properly, and we can coach you through the proper procedure when the time comes.”

Gathering Data

Getting the Cardinal back in the air was clearly going to take awhile, so Tony passed the reins to Tom Cooper A&P/IA, Savvy’s top breakdown assistance superhero. After a week passed with no word from Dominion, Tom pinged Jonathan for an update.

“Tom, we have been delayed getting back on the aircraft,” Jonathan reported. “We are in the process of cylinder removal now. I will keep you updated on our progress.”

The next day, Jonathan told Tom, “When inspecting the oil filter we found significant amounts of ferrous metal shavings and evidence the piston contacted the valve. Pictures attached. Please advise.” Jonathan attached a photo of the oil filter contents and the tip of a ¼-inch-diameter magnet with ferrous whiskers adhering to it, and another photo of the #2 piston crown exhibiting the obvious signature of an exhaust valve strike.

Tom and Jim discussed the situation at length. They were both surprised that the valve strike hadn’t been noted on the first day when the cylinder was borescoped. It would have been easily visible, but the technician who did the borescope inspection was apparently fixated on the exhaust valve and didn’t look at the piston crown.

Jim told Tom that Dominion was recommending that the engine be removed and shipped to an engine shop for a teardown inspection. “They estimated the cost at $30,000 or more, depending on what was discovered,” Jim said. “We would like to avoid this route if possible.” Tom agreed wholeheartedly.

Tom asked Jonathan to report back on:

- Whether the exhaust pushrod was bent

- The condition of the cam lobe and hydraulic lifter

- The quantity of metal found in the filter (was it ¼ teaspoon or more?) and whether it was all ferrous or mixed with non-ferrous

Tom and Jonathan had a telephone discussion, after which Tom advised Jim that:

- The valve is frozen in the cylinder.

- The piston has come into contact with the valve

- There is more than 1/4 teaspoon of ferrous metal in the filter

- The metal is very fine with no chunks noted

- The push rod has been bent

- The cam lobe and lifter don’t seem to be damaged

The next day, Tom advised Jim, “I have spoken to the shop and they are not comfortable with the notion of just replacing the piston and cylinder, given the amount of metal found in the oil filter. Jonathan wants to contact Lycoming for guidance and I’ve agreed. Lycoming’s opinion is not binding on us but simply another knowledgeable opinion. Let’s hold for a day or two to see what they have to say.”

Lycoming Weighs In

The next day, Jonathan told Tom, “I followed up today with Lycoming, who recommended we check the oil suction screen for contamination. We pulled the screen and found a few flecks of ferrous metal on the screen. We sent Lycoming a photo and we’re waiting for a response from them as to next steps to take. We will keep you updated.”

Tom recommended to Jonathan that the metal obtained from the oil filter and suction screen be sent to Aviation Laboratories in Houston for spectral analysis to determine the type of alloy involved.

Lycoming advised Jonathan: “Based on previous information as well as the new pictures, I am inclined to think Corrective Action 4 as listed in Lycoming Service Bulletin No. 480 F is appropriate.” (Decoded: SI 480 is Lycoming’s detailed instructions for what to do when metal is found in the oil filter, and Corrective Action 4 is a full teardown inspection.) “But would advise you to evaluate the material type, size, and quantity collected against table 3 as listed in SB480 to determine the recommended corrective action.” (That’s what Tom recommended when he suggested the metal be sent to Aviation Laboratories.)

With Jim’s concurrence, Tom asked Jonathan to send the metal obtained from the oil filter and the suction screen to Aviation Laboratories. Three days later, their report came back:

“The metal found in the chips sent as well as a minor amount of debris removed from the filter consist of alloy steel, closest match AMS 6270/6272, ranging in size from 377×293 to 5×3 microns.”

Decoding the AvLab report, AMS 6270/6272 alloy steel is a case-hardening steel containing nickel, chromium, and molybdenum as alloying elements. The only engine components made of this alloy are the camshaft and gears. While it’s possible that the cam lobe could have been damaged by the stuck valve, Dominion’s visual inspection of the cam lobe (with the cylinder off) indicated that there was no such damage.

Lycoming then weighed in again: “Due to the amount of material found and the type of material it is, I would recommend further disassembly of the engine to determine the origin of the material. If the operator chooses not to do this I would recommend performing Lycoming Service Bulletin No. 480 F Corrective Action 5.” (Decoded: Corrective Action 5 involves inspecting the spark plugs, borescoping the cylinders, and removing the prop governor to inspect the gasket screen for metal. The first two of these had already been done, and the last was not applicable because the Cardinal has a fixed-pitch prop and therefore no prop governor.) Lycoming continued, “If no findings are made, perform a ground run of the engine to determine if the engine is continuing to make metal. If ground run contamination check is satisfactory, return to flight and check for filter/screen contamination at no more than 5 hours.”

In plain English, what Lycoming was saying was: We’d prefer you to have the engine torn down, but if you don’t want to do that, then we suggest you ground-run the engine for a half hour, check the filter to see if the engine is making metal, and if it isn’t then fly for five hours and check the filter again to see if the engine is making metal.

Decision Time

Dominion was obviously more comfortable with Door Number One, while Jim and Tom were leaning heavily toward Door Number Two (whose price of admission was at least $20,000 less). After conferring by phone with Jim, Tom sent the following instructions to Jonathan:

“At this point, we have no direct evidence that the material has contaminated the engine. We ask that you perform SB 480F Corrective Action #5 (examine the spark plugs and borescope the cylinders), and that you install a new #2 piston and cylinder. Once the cylinder is installed, we will perform Corrective Action #2 (ground-run the engine for 20-30 minutes, cut and inspect the filter, if it’s clean we will fly the aircraft for 5 hours and then cut and inspect the filter again).”

Tom wanted to make sure that the ground-run test was valid and wouldn’t be compromised by any residual metal flakes or whiskers that remained in the engine. He therefore asked Dominion to flush the engine three times with mineral spirits before servicing it with break-in oil. Ever cautious, Dominion’s Director of Maintenance wanted Lycoming’s approval to do that. Jonathan checked with Lycoming and was told it would be okay. Jonathan proceeded with the engine flush, but was delayed because the engine sump plug was so tight that the shop needed to obtain a special socket to remove it without damaging the sump. Ultimately they were able to extract the plug and flush the engine. A small quantity of fine metal particles were flushed out.

Meantime, Jonathan sent Tom some borescope images of the other three cylinders (#1, #3 and #4). All of them looked quite worn with considerable vertical scoring, but since the compressions were all acceptable this didn’t represent an airworthiness issue, and Jim felt that he’d strongly prefer any further cylinder work to be done by their regular shop at KBMG.

“Borescope looks good,” said Jonathan, “We are going to install the cylinder.”

Lost Summer

By now, the Cardinal had been stuck at KFCI for two whole months during school break and prime flying season. Jim, Jack and Gene were anxious to get their plane home. They figured it might be another week, tops. They figured wrong.

The cylinder installation went smoothly enough. But a tropical storm delayed the ground run. When the shop was finally able to ground-run the airplane, they reported back that the oil temperature gauge was not registering and they’d need to troubleshoot it. A bunch of back-and-forth between the owners and their mechanic in Bloomington revealed that the factory oil temperature gauge never came off the peg until the airplane was at full takeoff power, but that the oil temperature sensor was also connected to channel #5 of the aircraft’s Electronics International US-8 eight-channel digital engine display, and that gauge registered oil temperature accurately.

Then the shop reported that one of the tow lugs on the nosegear was broken off and would need to be replaced.

FINALLY, 11 weeks after the Cardinal limped into KFCI on three cylinders, it had a new #2 cylinder and piston, had passed its ground-run tests with flying colors (clean filter), and was ready for its 5-hour break-in and making-metal-test period. Dominion’s invoice came to $3,800, which Tom told Jim he thought was quite fair in view of the work that was done. (Certainly, it was an order of magnitude less than what it would have been if the engine was sent out and torn down.)

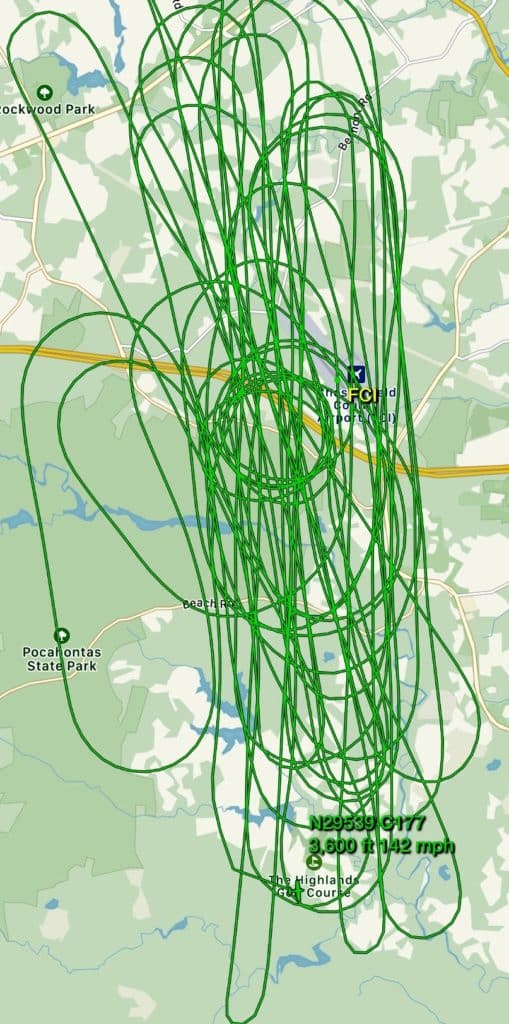

Jim travelled the 500 miles to Richmond to pick up the airplane. He wasn’t taking any chances, and opted to fly the first 3 ½ hours in the vicinity of KFCI before venturing out over the mountains. (Smart!) Here’s what that looked like:

“The following day after another oil filter inspection we topped off the fuel tanks and headed VFR to the west trying to skirt a front just west and north of KFCI,” Jim told Tom a few days later.” After about 45 minutes I contacted center and filed an IFR flight plan to Bloomington. It was mostly VMC with maybe a .1 of actual instrument conditions as I crossed the Appalachian mountains at 10,000’. Overall I was pleased with my aeronautical decision making. Our Cardinal is back home safe in the hangar ready for more adventures.”

“Airplanes can be expensive, and I’m sure glad I have two partners to help share the unplanned expense,” Jim concluded. “With the benefit of hindsight, we had plenty of warnings that the #2 exhaust valve was getting sticky. Classic ‘morning sickness’ symptoms. Our mechanic had to ‘stake the valve’ at the annual to get cylinder #2 to pass the compression test. We sure will pay more attention to such symptoms next time.”

“But it sure could have been a lot worse.,” he continued. “Dominion Aviation turned out to be a class operation. Every night and during inclement weather they had our Cardinal safely tucked into a hangar and out of harm’s way. They even washed the plane before I picked it up.”

“The fact that we’d enrolled the Cardinal in SavvyBreakdown before this happened and had Tom guiding us through this ordeal was a stroke of luck that saved us at least $20,000 if not more. We’ll never leave home without it again.”

Thousands of owner-flown aircraft use our breakdown assistance. While we can’t promise to save them all $20,000+, we can promise to be there for them 24/7 if and when they experience every owner’s worst nightmare, an aircraft breakdown away from home.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: