Every pilot understands the notion of “pilot in command.” That’s because we all had some certificated flight instructor (CFI) who mercilessly pounded this essential concept into our heads throughout our pilot training. Hopefully, it stuck.

As pilot-in-command (PIC), we are directly responsible for, and the final authority as to, the operation of our aircraft and the safety of our flight. Our command authority so absolute that in the event of an in-flight emergency, the FAA authorizes the PIC to deviate from any rule or regulation to the extent necessary to deal with that emergency. (14 CFR §91.3)

In four and a half decades of flying, I’ve overheard quite a few pilots dealing with in-flight emergencies, and have dealt with a few myself. It makes me proud to hear a fellow pilot who takes command of the situation and deals with the emergency decisively. Such decisiveness is “the right stuff” of which PICs are made, and what sets us apart from non-pilots.

Conversely, it invariably saddens me to hear a frightened pilot abdicate his PIC authority by throwing himself on the mercy of some faceless air traffic controller or flight service specialist to bail him out of trouble. How pathetic! The ATC or FSS folks often perform heroically in such “saves,” but few of them are pilots, and most have little or no knowledge of the capabilities of the emergency aircraft or its crewmember(s). They shouldn’t be placed in the awful position of having to make life-or-death decisions on how best to cope with an in-flight emergency. That’s the PIC’s job.

Fortunately, most of us who fly as PIC understand this because we had good CFIs who taught us well. When the spit hits the fan, we take command almost instinctively.

Owner in command

When a pilot progresses to the point of becoming an aircraft owner, he suddenly takes on a great deal of additional responsibility and authority for which his pilot training most likely did not prepare him. Specifically, he becomes primarily responsible for maintaining his aircraft in airworthy condition, including compliance with all applicable airworthiness requirements including Airworthiness Directives. (14 CFR §91.403) Unfortunately, few owners have the benefit of a certificated ownership instructor (COI) to teach them about their daunting new responsibilities and authority as “owner-in-command” (OIC).

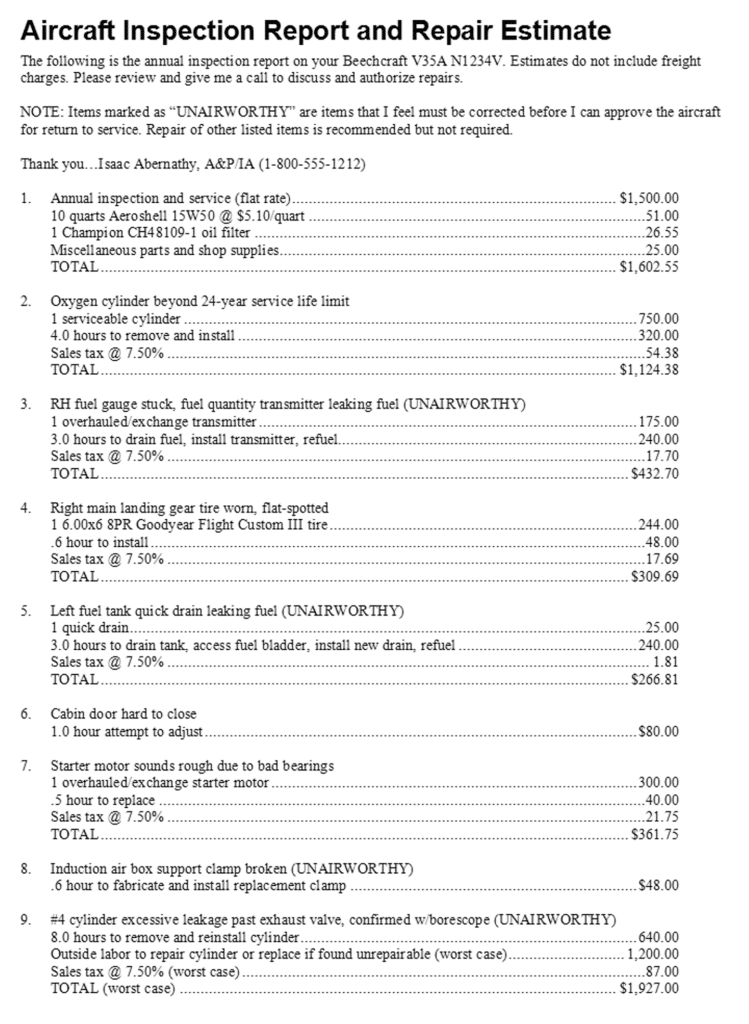

Consequently, too many aircraft owners fail to comprehend or appreciate fully their weighty and complex OIC responsibilities. They put their aircraft in the shop, hand over their keys and credit card, and tell the mechanic to call them when the work is done and the airplane is ready to fly. Often, owners give the mechanic carte blanche to “do whatever it takes to make the aircraft safe,” and don’t even know what work is being performed or what parts are being replaced until after-the-fact when they receive a maintenance invoice.

In short, most owners seem to act as if the mechanic is responsible for maintaining the aircraft in airworthy condition. But that’s wrong. In the eyes of the FAA, it’s the owner who is responsible. The mechanic is just hired help.

I find it helpful to compare the proper role of the aircraft owner in maintaining an airworthy aircraft to that of a general contractor in building a house. The general contractor needs to hire licensed specialists—electricians, plumbers, roofers, masons, and other skilled tradesmen—to perform various tasks required during the construction. He also needs to hire a licensed building inspector to inspect and approve the work that the tradesman have performed. But, the general contractor makes the major decisions, calls the shots, keeps things within schedule and budget constraints, and is held primarily accountable for the final outcome.

Similarly, an aircraft owner hires certificated airframe and powerplant (A&P) mechanics to perform maintenance, repairs and alterations; certificated inspectors (IAs) to perform annual inspections, and other certificated specialists (e.g., avionics, instrument, propeller and engine repair stations) to perform various specialized maintenance tasks. But, the owner is the boss, is responsible for hiring, firing, and managing these various “subcontractors,” and has primary responsibility for the ensuring the desired outcome: a safe, reliable aircraft that meets all applicable airworthiness requirements, achieved within an acceptable maintenance budget and schedule.

Who’s the boss?

The essence of the owner-in-command concept is that the aircraft owner needs to remain in control of the maintenance of his aircraft, just as the pilot needs to remain in control of the operation of the aircraft in-flight. When it comes to maintenance, the owner is supposed to be the head honcho, make the major decisions, ride herd on time and budget constraints, and generally call the shots. The mechanics and inspectors and repair stations he hires are “subcontractors” with special skills, training and certificates required to do the actual work. But the owner must always stay firmly in charge, because the buck stops with him (literally).

Since most owners have not received training in how to act as OIC, many of them are overwhelmed by the thought of taking command of the maintenance of their aircraft. “I don’t know anything about aircraft maintenance,” they sigh. “That’s way outside my comfort zone. Besides, isn’t that my mechanic’s job?”

Such owners often adopt the attitude that it’s their job to fly the aircraft and the mechanic’s job to maintain it. They leave the maintenance decisions up to the mechanics, and then get frustrated and angry when squawks don’t get fixed and maintenance expenses are higher than they expected.

But think about it: If you were building a house and you told your plumber or electrician or roofer “just do whatever it takes and send me the bill when it’s done,” do you think you’d be happy with the result?

No one in his right mind would do that, of course. If you were hiring an electrician to wire your house, you’d probably start by giving him a detailed list of exactly what you want him to do—what appliances and lighting fixtures you want installed in each room, where you want to locate switches, dimmers, convenience outlets, thermostats, telephone jacks, Ethernet connections, and so forth. You’d then expect the electrician to come back to you with a detailed written proposal, cost estimate, and completion schedule. After going over the proposal in detail with the electrician and making any necessary revisions, you’d sign the document and thereby enter into a binding agreement with the electrician for specific goods and services to be provided at a specific price and delivery date.

You’d do the same with the carpenter, roofer, drywall guy, paving contractor, and so forth.

Cars vs. Airplanes

If you’ll permit me to mix my metaphors, when I take my car to the shop for service, the shop manager starts by interviewing me and taking notes on exactly what I want done—he asks me to describe any squawks I have to report, and he checks the odometer and explains any recommended preventive maintenance. Once we arrive at a meeting of the minds about what work needs to be done, the shop manager writes up a detailed work order with a specific cost estimate, and asks me to sign it and keep a copy. In essence, I now have a written contract with the shop for specific work to be done at a specific price.

The service manager doesn’t do this solely out of the goodness of his heart. He’s compelled to do so. In California where I live, state law provides that the auto repair shop is required to provide me with a written estimate in advance of doing any work, and may not exceed the agreed-to cost estimate by more than 10% unless I explicitly agree to the increase. If the shop doesn’t follow these rules, I can file a complaint with the State Bureau of Automotive Repairs and they’ll investigate and take appropriate action against the shop. Most states have similar laws.

Unfortunately, there are no such laws requiring aircraft maintenance shops to deal with their customers on such a formalized and businesslike basis, even though the amounts involved are usually many times larger. Aircraft owners routinely turn their airplanes over to a mechanic or shop with no detailed understanding of what work will be done, what replacement parts will be installed, and what it’s all going to cost. All too often, the aircraft owner only finds this out when he picks up the aircraft and is presented with an invoice (at which point it’s way too late for him to influence the outcome).

It always amazes me to see aircraft owners do this. These are intelligent people, usually successful in business (which is what allows them to afford an airplane), who would never consider making any other sort of purchase of goods or services without first knowing exactly what they were buying and what it costs. Yet they routinely authorize aircraft maintenance without knowing either.

Often, the result is sticker shock and hard feelings between the owner and the shop. There’s no State Bureau of Aircraft Repair to protect aircraft owners from excessive charges or shoddy work. The FAA almost never gets involved in such commercial disputes. A few owners even wind up suing the maintenance shop, but generally the only beneficiaries of such litigation are the lawyers.

You can’t un-break an egg. You’ve got to prevent it from breaking in the first place.

Trust But Verify

I hear from lots of these disgruntled aircraft owners who are angry at some mechanic or shop. When I ask why they didn’t insist on receiving a detailed work statement and cost estimate before authorizing the shop to work on their aircraft, I often receive a deer-in-the-headlights look, followed by some mumbling to the effect that “I’ve never had a problem with them before” or “you’ve got to be able to trust your A&P, don’t you?”

Sure you do…and you’ve got to be able to trust your electrician, plumber and auto mechanic, too. But that’s no excuse for not dealing with them on a businesslike basis. Purchasing aircraft maintenance services is a big-ticket business transaction, and should be dealt with as you would deal with any other big-ticket business transaction. The buyer and seller must have a clear mutual understanding of exactly what is being purchased and what it will cost, and that understanding must be reduced to writing.

In coming issues of EAA Sport Aviation, I’ll explain exactly how this should be accomplished. I’ll talk more about how owners and mechanics can work as a team to achieve better maintenance at lower cost, and suggest various money-saving maintenance strategies. I’ll also discuss the owner’s role in troubleshooting and maintenance decision making. Stay tuned.

In the final analysis, however, the most important factor that sets a maintenance-savvy aircraft owner apart from the rest of the pack is his attitude about maintenance. Savvy owners understand that they have primary responsibility for the maintenance of their aircraft, and that A&Ps, IAs and repair stations are contractors that they must manage. They deal with these maintenance professionals as they would deal with other contractors in other business dealings. They insist on having a written work statement and cost estimate before authorizing work to proceed. Then, like any good manager, they keep in close communication with the folks they’ve hired to make sure things are going as planned.

If your mechanic or shop resists working with you on such a businesslike basis, you probably need to take your business elsewhere.

You bought a plane to fly it, not stress over maintenance.

At Savvy Aviation, we believe you shouldn’t have to navigate the complexities of aircraft maintenance alone. And you definitely shouldn’t be surprised when your shop’s invoice arrives.

Savvy Aviation isn’t a maintenance shop – we empower you with the knowledge and expert consultation you need to be in control of your own maintenance events – so your shop takes directives (not gives them). Whatever your maintenance needs, Savvy has a perfect plan for you: