While channel surfing recently I tuned into the opening scene of 12 Angry Men. It had been years since I had seen it, so I decided to give it a go. It’s not a flashy movie, it’s in black-and-white, and except for the final scene on the courthouse plaza, the movie takes place in one small jury room. The artistry of the movie is the story, the acting, the camera placement, and the editing. Henry Fonda leads a powerhouse cast trying to reach unanimous verdict in a murder case. On the first vote, 11 vote guilty and Henry votes not guilty. Spoiler alert: over the course of the movie Henry stands his ground, questions the evidence and one by one the other jurors re-think their positions and change their votes. In the end they all vote not guilty and go home.

My uncle used to say about my aunt that she got most of her exercise by jumping to conclusions. We’ve all probably encountered a mechanic who heard a phrase or two and was immediately convinced of what was wrong with the airplane. Psychologists call it confirmation blindness — our tendency to accept evidence that supports our conclusion and reject evidence that doesn’t. Unfortunately, many of us have paid the bills for incorrect conclusion jumping. Fortunately, engine data analysis is helping us avoid costly rabbit holes and fix only what needs fixing.

The Rest of the Story

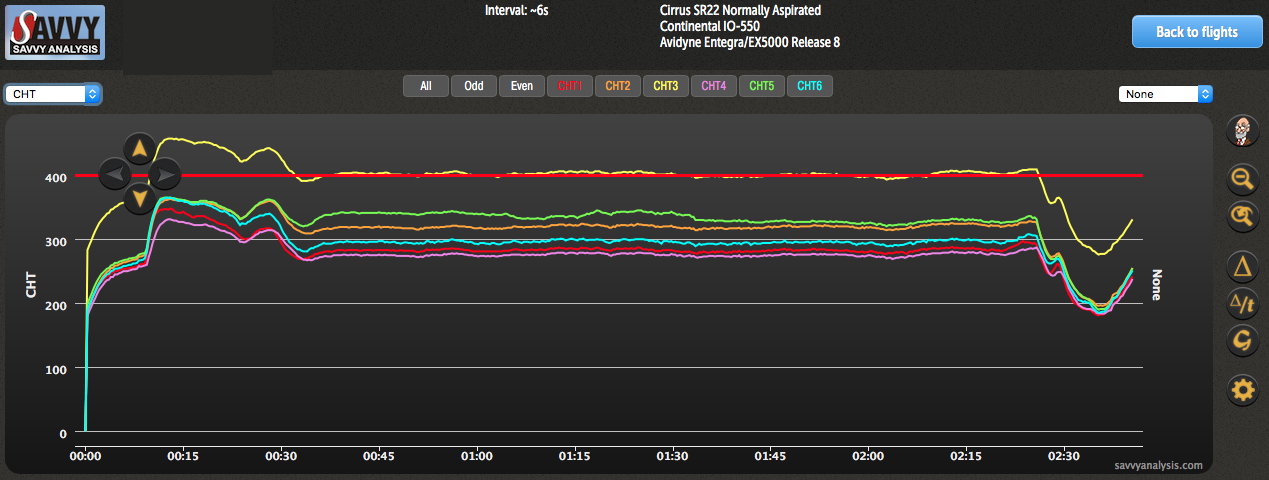

With a healthy dose of Henry Fonda skepticism, let’s look at CHT data from an SR22.

This is scary. The yellow trace starts out hot, peaks well above 400º, and settles in around 400 in cruise. EGT 3 (not shown) is normal, so we should be able to rule out an excessively lean mixture. What would cause that cylinder to make heat like that? A broken ring generating internal friction? A missing inter-cylinder baffle? CHT 5 (upstream from the heat) is a little high, and CHT 1 (downstream from the heat) is happy in the pack. So far nothing is corroborating the heat. Let’s look at previous flight data from the same airplane.

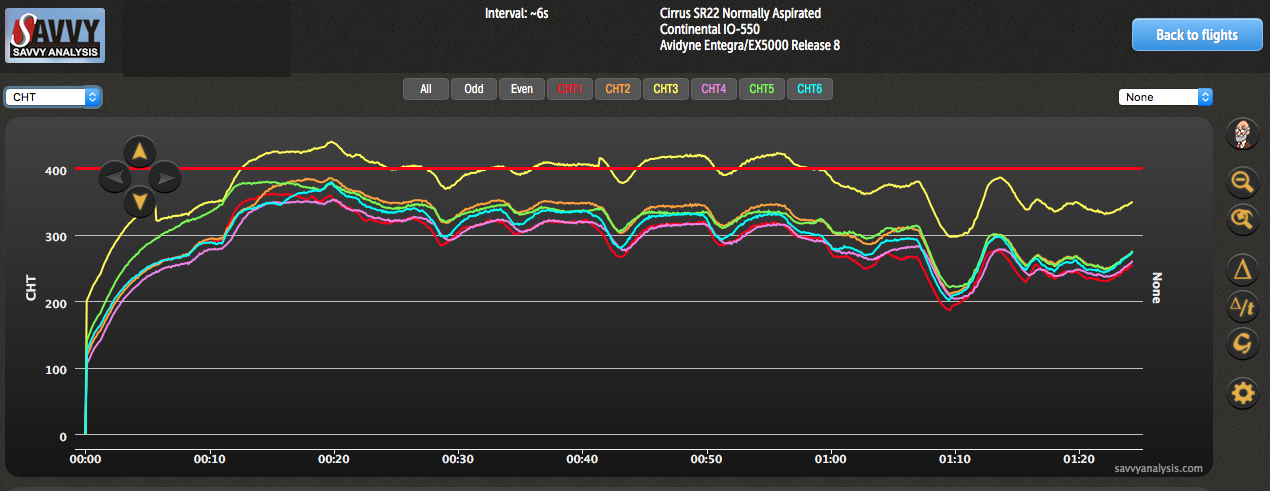

Look at the trace after engine start. The down arrow is partially blocking the data, but you can see an almost vertical drop in the yellow trace – something that shouldn’t happen with a CHT. Then for a couple of minutes it looks like it’s tracking normally, before resuming its dance around the red line. Could a bad ring do that – behave momentarily then resume generating heat? Maybe. Could a missing baffle part do that? No.

Plus, there’s the issue of the quick decline of CHT. Even with our sample rate of 6 secs, that sort of thermal dispersion seems unlikely. Is there more data to look at?

Facts not yet in Evidence

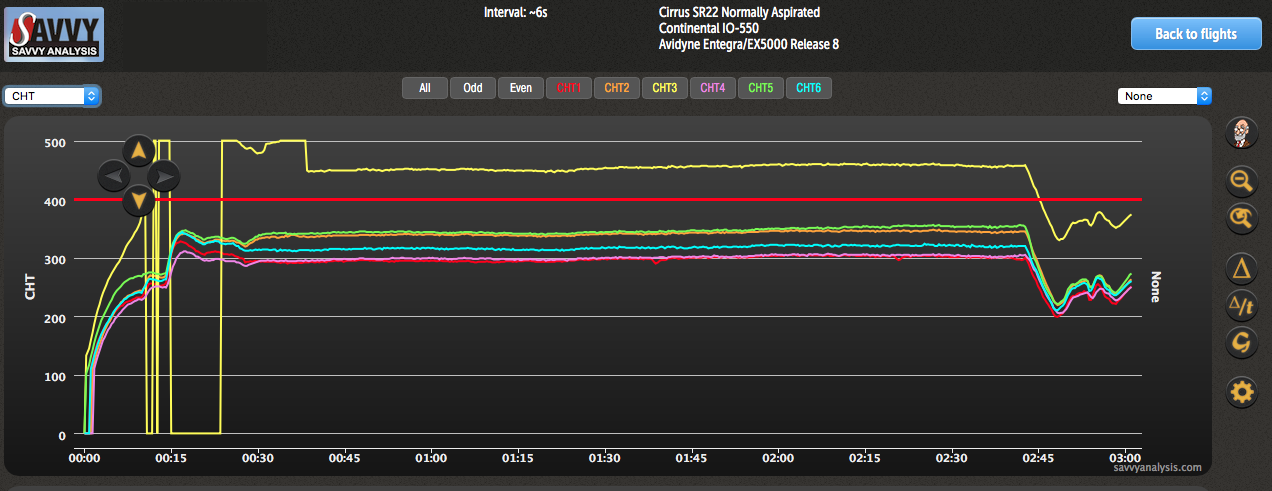

Unanimous verdict returned. It’s a bad probe. The confounding thing that made this analysis a puzzler is that we saw the flight data in this order. First came the normal-looking but very high data, then the one with the question mark, then the one with the answer. The probe failed spectatularly with spikes to zero and 500, then stubbornly hung around sending bad data that was plausible enough to believe. Airplane owners hardly ever root for catastrophic failures, but probes may be the exception. Instead of 12 Angry Men in the jury room nuancing the facts of the case, we want probes to have those Perry Mason moments in the courtroom – stand up and yell “I’m guilty. I did it.”

The advantage of juries over judges is supposed to be the added life experience of the panel. You can add this probe’s behavior to our life’s experience. Before this event, I’m not sure we had irrefutable evidence that a probe would announce failure, then return to service. So that experience came in handy when this data showed up.

CHT 2 – the brown trace – indicates a detonation-looking event, then a slow descent back to normal range. EGT 2 stands its ground, arguing against a thermal runaway in the cylinder. Before the event, CHT 2 is about 370º, which would be on the low side for detonation to begin. So the jury’s out, but leaning toward a probe malfunction. Not recommending borescoping the cylinder solely on this data.

Here’s the data from the subsequent flight.

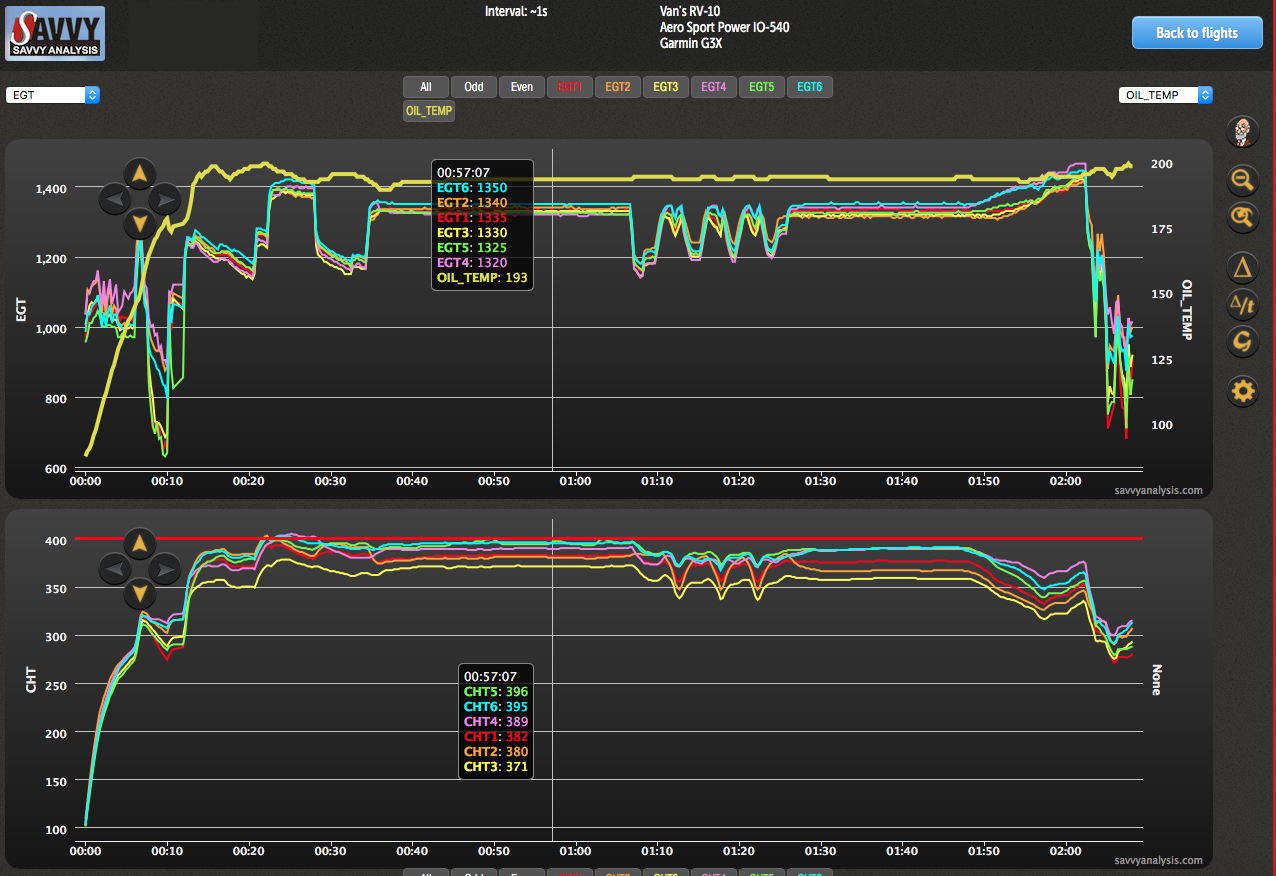

CHT 2 shows a brief excursion from the pack just left of the cursor – otherwise normal. In a case like this we make a note of the probe and see what develops over time. But it’s on – pardon the pun – PROBation, and any subsequent offense will be treated seriously. EGT 4 – the purple trace – looks like it’s starting to fail.

Now let’s deal with the big elephant in the EGT room. What are those two giant engine-quitting spikes where all EGTs drop to zero? Twice!! Here’s your clue – look at where they occur on the timeline. Is there a pattern there? They’re several minutes before landing, they’re a few minutes apart, and there’s no corroboration in CHT (or the pilot’s report) that the engine quit. This is an SR22, so fixed gear. But there is another electrical event that usually occurs prior to landing and often in two stages.

Flaps. There was a grounding issue with the flap motor that took out the EGT sensors when it was in motion. New ground strap = happy EGTs.

Sometimes the answers are obvious. Sometimes they’re there, but you have to dig for them, as with the CHT above. Sometimes you have to look beyond the fact itself and put it in context. In the movie, Henry Fonda was an architect. He would’ve been a good analyst.

12 Angry Men was produced in 1957. Even with that powerhouse cast, no actors were nominated. Alec Guiness won best actor for Bridge on the River Kwai. Director Sidney Lumet was nominated but lost to David Lean for Bridge. ’57 was a good year for airplane movies, though. Wings of Eagles, Zero Hour!, Jet Pilot and Bombers B-52 kept actors and stunt pilots busy that year. Sky King was in his heyday flying his 310 on Saturday mornings. And CBS premiered Perry Mason on September 21, 1957.