If you can have latitude in your attitude, then a properly-timed set of mags can have – magnetude. I guess it can have magnitude, too, but this column’s about the good, bad and ugly of mags and ignition spark. The EGT pattern of a perfect mag check can be a beautiful thing. But the analysis team is often summoned because things aren’t perfect, and we have to figure out why.

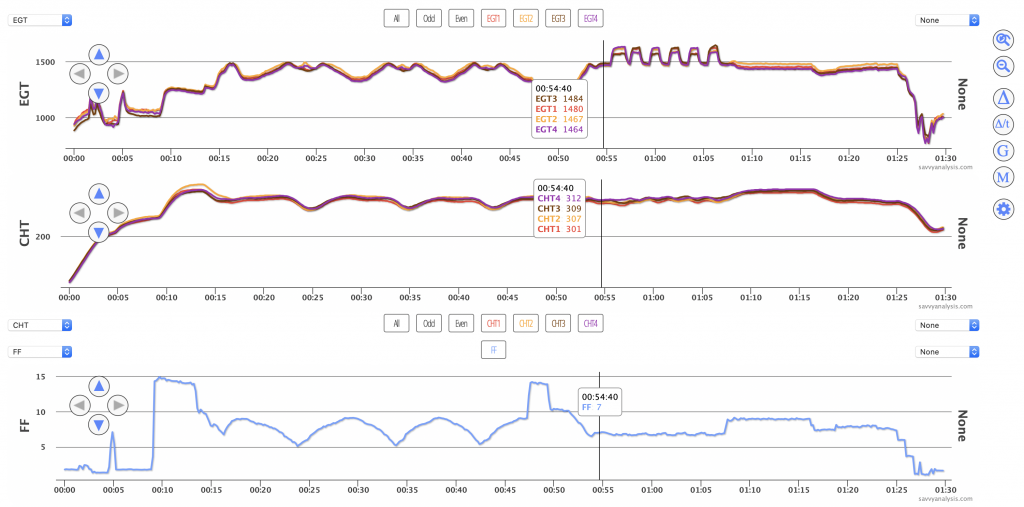

Let’s start with data from a 2013 Cessna 172 with a Lycoming IO-360 and data from a Garmin G1000. This is the whole flight with EGTs on top, CHTs below and FF below that. I always start here to be sure that FF is consistent throughout the mag check.

I won’t take the space to show you here, but I have lots of examples of FF changing when the pilot switches to a mag with weak spark and the engine gets rough. Some pilots switch back to both mags, some reach for the red knob. We see it all the time, it’s a perfectly natural reaction and will get no criticism from me – but we don’t want to draw conclusions from the data. In this case FF is steady so let’s zoom into the mag checks using the M tool.

Back in 2013 when these tools first appeared, we didn’t have this M tool to isolate and separate the odd and even cylinders. We did it manually by changing the second rank from CHT to EGT, then isolating the odds on the top rank and evens on the second rank, so you can see what a timesaver the M tool has been over these past years.

Our test profile asks for one good set of isolated mags. This pilot gave us three. We’re content with one good set, but if you have the time to give us two or three, we’ll take it. In this example we see small changes from one set to the next – we already ruled out FF as a factor – and if we’re going to recommend maintenance which cuts into your dispatch reliability and might cost around $100 an hour, the more confidence we can have in our recommendation, the better. This set of checks takes about 12 minutes.

Conversely, this is a good time to remind you that there’s no need for a pilot and passengers to suffer through a rough ride to get this data. If you isolate a mag and it’s really rough – underwear rough – then abandon the test. There’s a good chance we already got the data we needed when one of the EGTs spiked way up or way down. We like to have 10 contiguous samples. For this this Garmin that’s 10 seconds per mag. For an older Avidyne sampling at 6 seconds it’s a minute. Our test profile also has instructions on what to do if the engine quits when you isolate a mag.

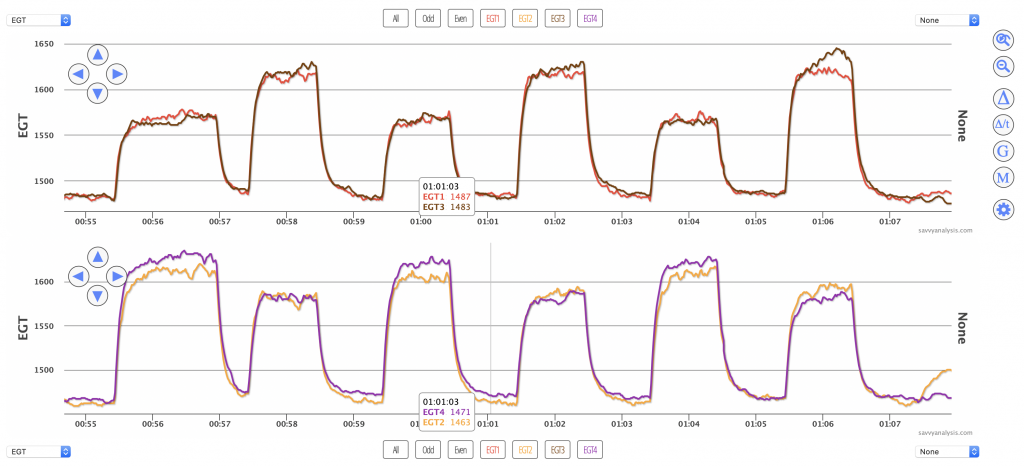

Sometimes an analysis request will come with a comment that “the EGTs were higher on one side on the L mag, then the other EGTs went higher on the R mag.” That, my friends, is Magnetude. With a conventional two-mag system with one mag firing the top plugs of one cylinder bank and the bottom plugs of the other, combustion from the bottom plugs only will be slower and result in a higher EGT. That’s what we want.

Exceptions —

- the spec for RAM engines uses a 2º difference in timing so the pattern isn’t as symmetrical as in the 172 in the example

- some engines are wired to fire all the tops from one mag and all the bottoms from the other

- electronic mags that change timing based on powerplant settings

This 172 shows all plugs firing and mags closely timed. They might both be slightly advanced or slightly retarded – that’s a subject for another Puzzler someday – but they’re closely timed vs one another.

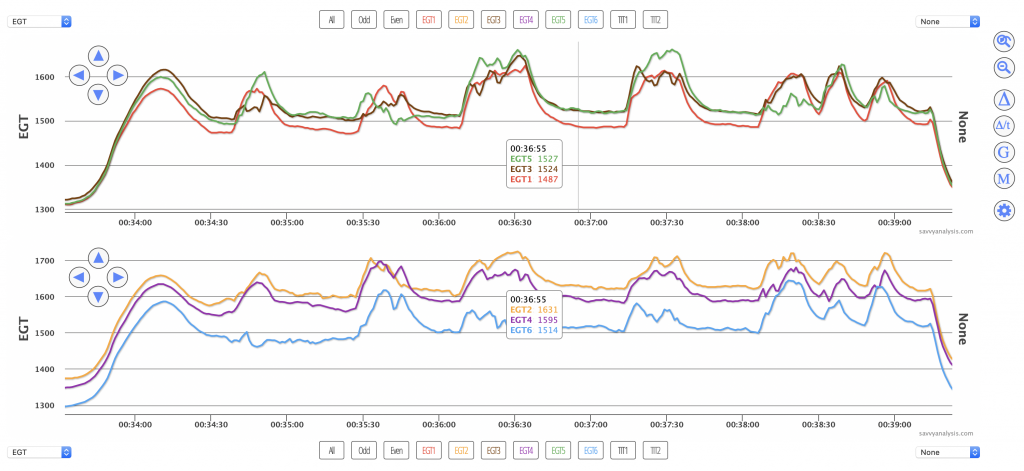

Here’s data from a Cirrus SR22T with a Continental TSIO-550-K and data from a Garmin Perspective with a 1 sec sample rate.

At first glance it looks like the drop from bottoms to tops on 1-3-5 in the top rank is larger than the rise from tops to bottoms on 2-4-6 in the lower rank. I used our 𝚫 tool to calculate the difference. If you ignore the ± signs, the numbers are higher for the odds than for the evens. So this looks like a case of slightly mis-timed mags.

If this airplane were on its way to scheduled maintenance, like an annual, we’d recommend checking the timing. If not, what we’re seeing here is not enough to recommend pulling the airplane from service. We would check it again in a few months or if roughness develops.

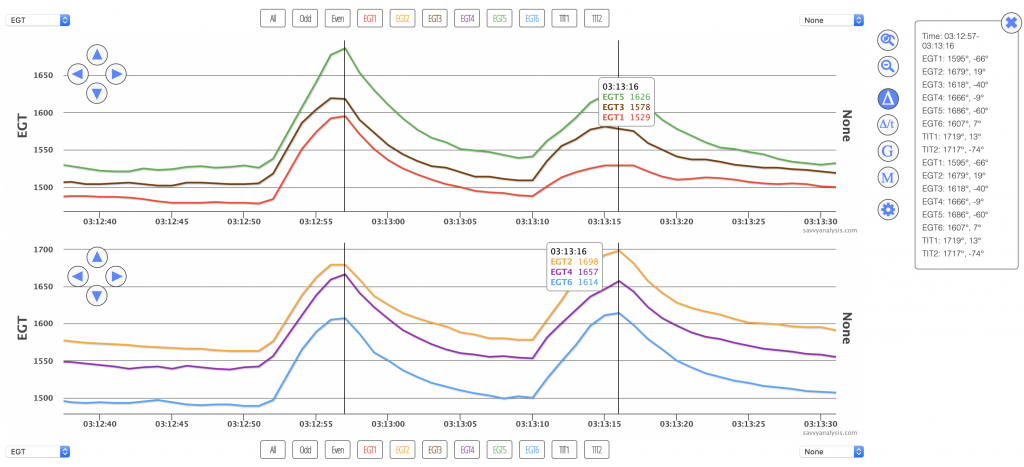

Here’s data from a normally aspirated SR22 with a Continental IO-550-N and data from a Garmin Perspective with a 1 sec sample rate. I gave this one some “handles” before and after so you could see the trace with both mags firing, too.

This plane just came out of annual, so it looks like a MIF – maintenance-induced failure. The traces are so weird it’s hard to tell the tops from the bottoms, but the best guess is the first mag checked is the R which fires the tops of 1-3-5 and the bottoms of 2-4-6. In that case it’s the top plugs of 3, 4 and 5 that need attention.

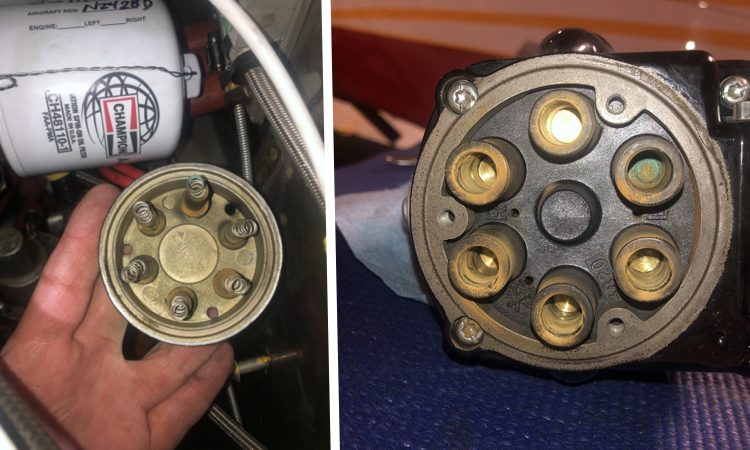

The owner of an RV-10 submitted data that showed weak spark on cyl 6. The plugs looked ok so he pulled the cover from the mag and saw this.

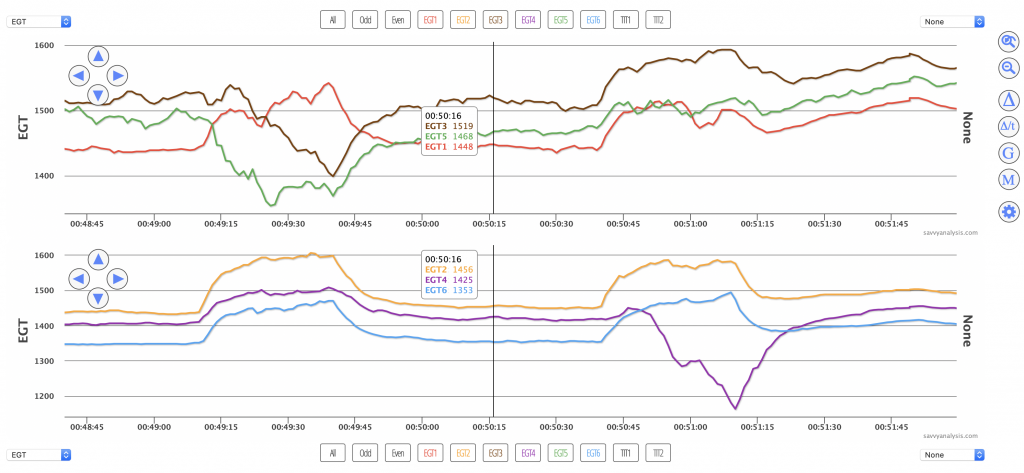

Here’s a series of checks from a Cessna 400 with a Continental TSIO-550-C and data from a Garmin G1000 with a 1 sec sample rate.

Again, hard to tell the tops from the bottoms. This test is after the plugs of 5 were moved to 6 as part of troubleshooting. Now it looks like 6 needs work, but 5 is clearly not healthy either.

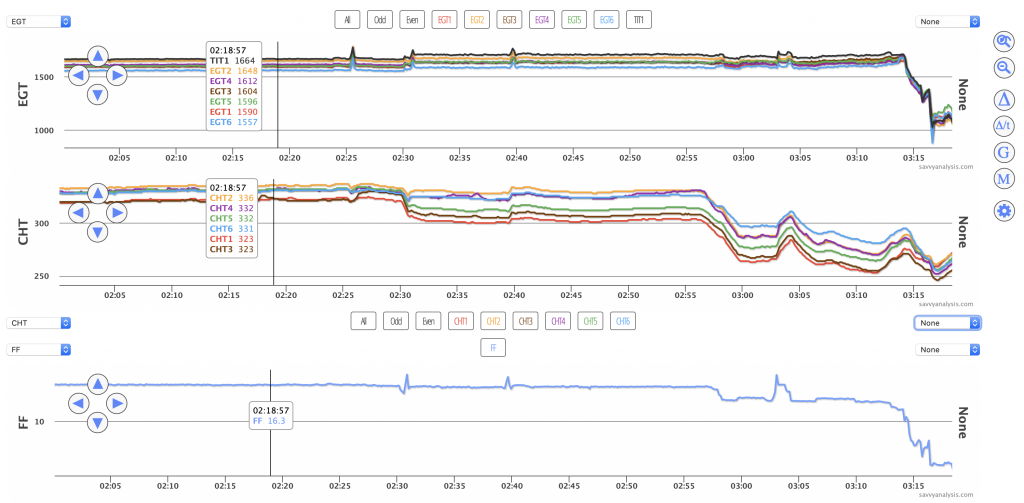

We’ll finish this month with a Mooney M20V Acclaim with a Continental TSIO-550-G and data from a Garmin G1000 with a 1 sec sample rate. It’s a 3 hour flight – this is the last hour or so. Let’s make this one a Puzzler – you guess what’s wrong.

Your hint is that this Puzzler is devoted to mags, so if you guessed mag failure, good on you. It’s not everyday we get to see a mag failure in flight – but here it is. The cursor is well ahead of the event which appears to begin at 02:25 in the timeline with CHT 3 moving higher. (CHTs 1 and 3 had been low as depicted up to this point.) Around 02:25 EGTs jump but FF doesn’t, and CHT 3 pulls away from 1 to join the others.

Then about 5 mins later CHTs 1-3-5 dive, all EGTs rise, and there’s a brief spike in FF. More than likely that’s the pilot’s instinct to reach for the red knob in reaction to the roughness. Altitude isn’t depicted, but he’s at 17,000 in cruise, and stays there on one mag until descent for approach at around 02:55. Fortunately, it’s an uneventful approach and landing.

I’ll pose a question for discussion if you’re so inclined. Let’s say you’re cruising at a typical cruise altitude for you and your plane – whether that’s 5,000 or 15,000 or whatever it is. And this happens and you determine that a mag has failed. But the engine seems to be running fine on one mag.

Do you return to base, continue on to your planned destination, or divert to the closest field? Does it depend on who’s in the plane with you? Does it depend on how familiar you are with maintenance options behind you, ahead of you and below you? Does it depend on whether you’re VFR or IFR? Do you declare an emergency?